When the news landed, I was surprised but not shocked. One of my Learners, Rita Cappello, had won the prestigious award for the Highest Marks in the World for Pearson A-Level English Language and Literature June 2024 exam. I knew Rita was brilliant now I realise she was top-of-the-world brilliant.

Gifted and talented Learners, I have encountered plenty. But what made Rita unique? She started out, as many Learners do, passionate about reading and well read. Bonus points: she had impeccable IGCSE results, which gave her a strong foundation for bridging the notoriously difficult gap between GCSEs and A-Levels. Anyone in the know will tell you—it’s one of the hardest transitions.

Being SMART about targets

SMART targets are the holy grail in all walks of life, and Rita wielded them like a knight on a quest. She tracked her progress with short-term goals, constantly defining and redefining them to ensure she mastered both the information and skills she needed—on time.

Like any Learner, Rita missed deadlines—not because she was disorganised, but because juggling A-Levels while running a charity is demanding. However, by taking full ownership of her timeline, she could anticipate when to negotiate extensions and adjust her calendar to fit in what she had missed.

Turning feedback into fuel

Learning is not linear. There are learning curves and learning pits before we get to mastery, and I feel that Rita understood this better than most. Many educators bemoan the fact that learners look at feedback as a box ticking process.

Too often, the focus is on the grade achieved rather than the learning process itself. Learners scan feedback for key words that quantify progress instead of engaging with it meaningfully. To counter this, many advocate for summative feedback over grading, encouraging students to see feedback not as a hurdle to clear but as a springboard for improvement.

This also speaks to resilience. Guys, feedback fatigue is real. As a daughter of very demanding parents, I know how it feels to always fall short. I understand just how frustrating it can be for Learners when they continuously receive feedback for improvement. It’s easy to feel defeated when the grade doesn’t match their expectations. Yet, in a hybrid environment, how else can we facilitate learning if not through feedback?

In an online learning context, the frustration is amplified. There are no opportunities for me, as the teacher, to soften the blow—no chocolate bar to numb the disappointment, no quick cathartic chat in the corridor, no pep talk in the canteen to help Learners see the value in their mistakes. All I have are my written feedback and Office Hours and through them, I must convince learners that their mistakes are not failures but essential steps in the learning process.

But Rita understood this. She pored over her feedback, zooming on the details with precision and intent. Sometimes, even when a second submission didn’t go as well as she had hoped, she sought me out—not just to ask for clarification but to ensure she fully understood what she needed to do next.

Learning how to learn

Many of the ambitious, bright Learners who struggled to succeed weren’t failing due to a lack of intelligence—but because they didn’t fully understand how they learned. Put simply, they didn’t know how their brains processed information or what strategies helped them retain large volumes of it.

This is especially true for Learners who excelled at GCSE and who are naturally gifted. Because they've never had to actively repackage or process information, they run on autopilot—absorbing knowledge without deeply engaging with it. So when faced with overwhelming amounts of complex material, they hit a wall. They simply don't know how to learn. Many talk about students plateauing after GCSEs, and much of this comes down to how well a Learner understands and masters their own cognitive processes.

Rita understood what worked for her, and when the exams demanded skills she had not yet mastered, she experimented with different techniques, adjusting and refining them along the way. By recognising her strengths and weaknesses early, she was able to develop strategies that leveraged her strengths and mitigated her weaknesses effectively.

Communication is the master key

Many still confuse online learning with anonymous learning. Hybrid and asynchronous learning environments offer Learners the freedom and flexibility to study anytime, anywhere, but they also place the responsibility on the learner to manage their interactions with the course tutor.

Switching from a traditional classroom—where I could call a Learner by name and check their understanding instantly—to an online setting was a shock to the system. Now, I have to wait for the Learner to choose to engage with me. Relinquishing control over checking learning was incredibly difficult to navigate.

If there was a Murphy’s Law for teens, I think it would be, "the more they need help, the less they’ll say so." Speaking up when they have doubts or misconceptions is especially difficult for teenagers. In a traditional classroom environment, the Learners can avoid make eye contact; in online learning, they ignore their emails and messages.

Rita, on the other hand, never stopped asking questions. She didn’t just seek answers—she used questions to make sense of her thought process. These questions were both to clear up misconceptions and to confirm her understanding. Just the act of talking (often typing rather) her thoughts facilitated her lightbulb moments.

Intellectual Curiosity

Another version of Murphy’s Law for teens might be: Teenagers will communicate their deepest thoughts and feelings—but in the most inconvenient ways possible.

In that respect, creating a safe space for intellectual curiosity is fundamental to helping Learners realise what they don’t know—until they do. Most of Rita’s deep learning happened in those interactions where she was able to verbalise and clarify her own thoughts. The diligence with which she prepared for our conversations is a testament to her dedication to mastering the subject.

The Real Lesson

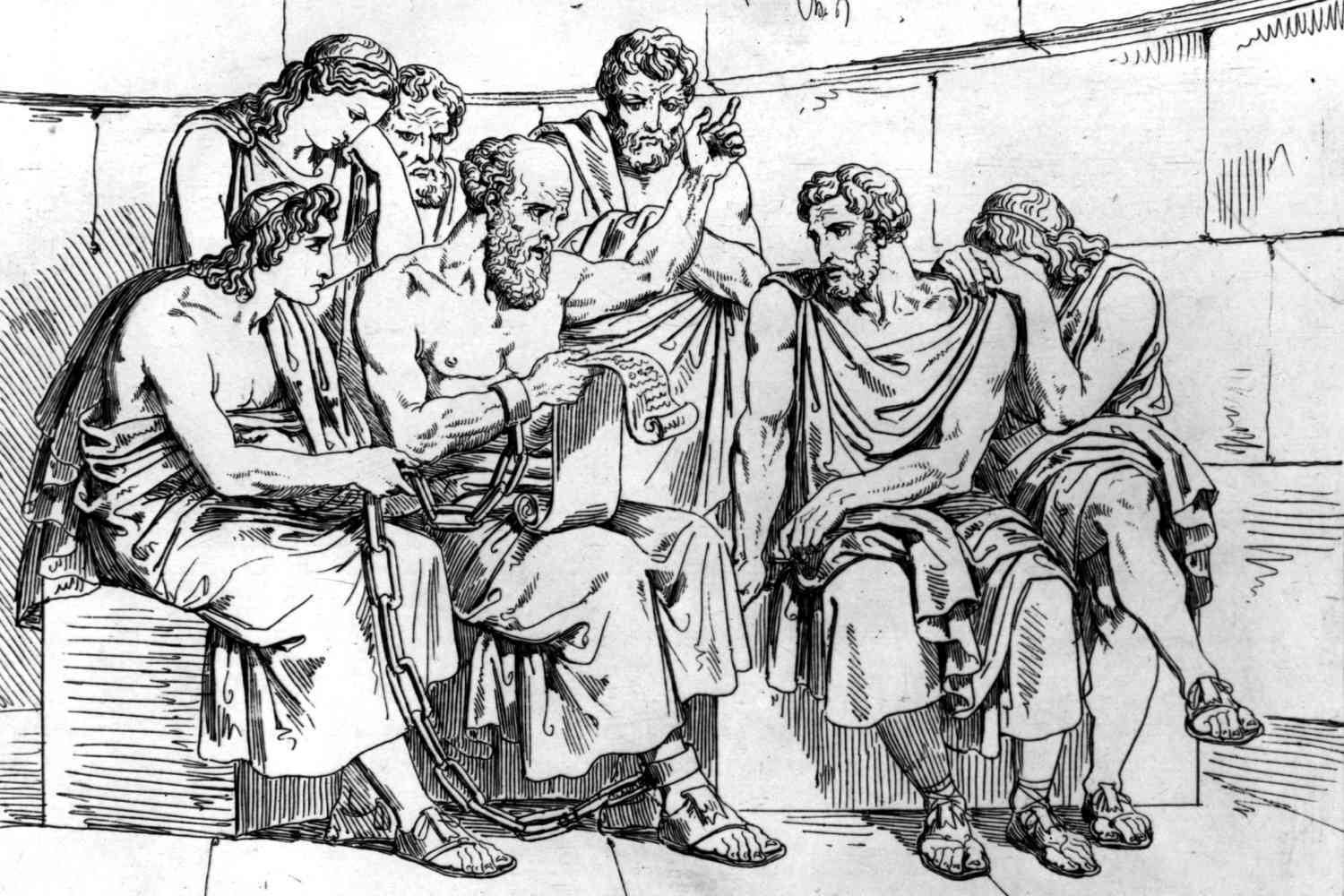

So, what did I learn from Rita? I learned that Socratic questioning is anything but outdated—even in a hybrid, asynchronous learning environment, its strategic use remains as valuable as ever. Many of our conversations took place on Moodle, Teams and during Office Hours. These were instigated by the written feedback she received. And, while these sessions helped Rita refine her understanding, they also helped me refine my own teaching materials.

Winning the title was never Rita's purpose. No one studies A-levels with the aim of becoming the best Learner in the world, but mastering how to learn—the very essence of the Socratic method—is the key to lifelong success.

This article is originally written by Geraldine Bhoyroo, English Language & Literature Course Manager at BGA. You can read the original article here.

Leave a Comment